Scarcity Blog (Part Two) Published

I have just published the longer and I hope more interesting installment of my two-part blog on behavioral economics and in particular, on the implications of the arguments made in the book Scarcity for microfinance and more broadly for international development. It includes a brief analysis of Fonkoze’s CLM (“Pathway to a Better Life”) program through the behavioral economics lens.

Full Financial Inclusion, Defined

The Center for Financial Inclusion (on whose Advisory Council I proudly serve) has done a great service by defining a very important concept: “full financial inclusion.” They have not, however, made it easy to find that definition online so I have taken it upon myself to create this blog post with the single purpose of reproducing their definition, which is (in its most recent formulation):

Financial inclusion means that everyone who can use them has access to a range of quality financial services at affordable prices with convenience, respect, and dignity, delivered by a range of providers in a stable, competitive market to financially capable clients. Quality and access are the double heart of CFI’s vision.

Scarcity Blog (Part One) Posted

As promised in my last blog, I have written a two-part blog on the behavioral economics-based analysis of scarcity in an important new book. Part one has been posted today on the Grameen Foundation blog. Part two will be published later this week.

Understanding Scarcity

One of the things life has taught me is if you want to do anything meaningful and/or difficult with someone else, it is vitally important to try to see the world, or at least your hoped-for collaboration, through their eyes. This is true regardless of whether or not you agree with how they are viewing things. Simply understanding their point of view is a great asset. (In fact, I think it is more important if you don’t agree with them.) Sometimes people won’t tell you what how they see things. Sometimes they don’t even know themselves. But with effort — usually in the form of asking some questions and simply giving it some thought — it is possible to get a good sense of where people are coming from and how they view you and the collaboration.

If you are reading this blog, you probably have wondered how the world looks from the perspective of a poor woman in Haiti. Trying to be helpful to them through involvement in organizations like Fonkoze is easier if the end clients’ worldview is not totally foreign to you. That is true whether you are delivering a product or service to their doorstep or trying to spread the word about organizations like Fonkoze in your church or Rotary Club (to cite just a couple of examples).

Perhaps you have even interviewed Fonkoze clients, or other beneficiaries of microfinance or other anti-poverty programs, or just had an informal chat with a random person whose socio-economic status was well below yours. Or maybe you have read accounts of, or talked to, people who have conducted such interviews. (My book Small Loans, Big Dreams tries to allow the reader to get intimate view into the lives of low-income women in rural Bangladesh and urban Chicago. The book Portfolios of the Poor adds many additional insights.)

It is possible to get fairly deep insights into how the world looks through the eyes of a poor person by interviewing them at length and observing them as they go about their lives. However, initial perceptions are often incomplete, or flat out wrong. In my interviews in Bangladesh, I was learning new information a full two years after I began talking to the women about whom the book is written. I also think it is useful to simply give some considered thought to the world looks to a poor person, even without conducting any interviews or reading.

Another way to approach this objective is through the emerging field of behavioral economics, which is basically the intersection of psychology and economics. I have just finished an excellent book titled Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir. It attempts to study the phenomenon of scarcity through the behavioral economics lens.

Poverty is a special case of scarcity, but their approach and findings are more general. They also apply to scarcity of time (i.e., people who are too busy) and scarcity of human contact (i.e., people who are lonely), for example. It turns out that the phenomenon of scarcity impacts the human mind and capabilities similarly regardless of what is scarce, and whether the person is rich or poor, male or female, Asian or American.

Their analysis explains a lot about why people under conditions of scarcity behave in certain ways, and do not behave in other ways. In short, this condition enhances some capabilities but deforms others – in a fairly predictable manner. For microfinance and human development generally, there are some important implications for practice. In some cases, this analysis confirms and explains long-held assumptions. In other cases, it challenges prevailing assumptions and current practice.

I also recall writing a blog about abundance in Haiti. It turns out that abundance is related to scarcity in some important and unexpected ways.

I will be writing a blog about this book and what its implications are for holistic, double-bottom-line microfinance in the days ahead. If I do not post it on this blog, I will certainly link to it. I encourage feedback and ideas, both before and after posting these reflections.

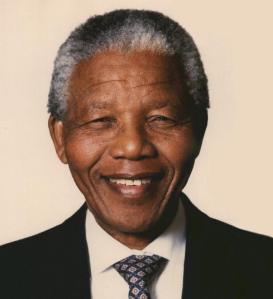

Nelson Mandela, and Father Joseph

As I read all the tributes to Nelson Mandela in the wake of his death yesterday at age 95, I recalled the fact that I memorably met the man once. It was at a small and magical dinner hosted by the philanthropists Craig and Susan McCaw in their Seattle home in the late 1990s.

In fact, I was one of two non-profit leaders asked to speak at this event attended by two dozen leaders from the worlds of business, philanthropy and government. A bit nervous as one can imagine, I gave a short talk on my work with Grameen Foundation. (Among those I met that night were the sitting Governor of the state of Washington and Bill Gates, but Mandela’s presence was what made the night so unique and thrilling.)

After each course was served and cleared, people were asked to move from one table to the next. This way, everyone got some time with Mandela and his wife, Graca Machel. By that time, Mandela was rather hard of hearing so it was not easy to engage him in conversation. But just sitting with him at a table for eight people for twenty minutes was quite something.

I see a lot in common between Mandela and Father Joseph Philippe, the founder of Fonkoze. Both are/were great moral leaders and men of action. Both are savvy (and occasionally infuriating) negotiators, practical visionaries, sometimes rather stubborn, and impossibly generous of spirit. Both emerged from their years in the wilderness – Mandela’s spent in prison, Father Joseph’s biding his time until the Duvalier dictatorship fell – and immediately started building movements to create social and political change. Clearly they are also different in many ways.

One of the stories that I hope gets told about both as people reflect on their lives is that of the friends, helpers, and “intrapreneurs” around Mandela and Father Joseph who were essential in allowing them to realize so many of their visions, even if not always in the exact forms they initially imagined.

Tributes to Anne Hastings

Last Thursday, I attended an event honoring and celebrating Anne Hastings’ 17 years of service in Haiti, as she recently transitioned into a volunteer and governance role. Of the hundreds present, 12 people invited to speak for three minutes each — some Haitians, some foreigners, some in Creole, some in English. Father Joseph, Julian Schroeder, Leigh Carter and Maryann Boord also spoke, sang and presented a nice slideshow and some gifts. I was one of those 12 speakers. Later, I wrote up my remarks based on my notes and my best recollection of what I said (and a few things I meant to say but in the moment, omitted). Anne did not encourage me to publish my remarks, even though she did ask me to write them up for her personal use and files. But when asked, she gave me her blessing to put them on this blog.

I have had the privilege of meeting and working with hundreds, and probably thousands, of people who have dedicated a major part of their lives to humanitarian causes and in particular, to the reduction and elimination of poverty. Many of them are in the room here tonight. Among all of these amazing people, two stand apart. They are a different breed, almost a different species.

One is Nobel laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus. The other is Anne Hastings. There have been many others on par with them throughout history, but these are the two I have gotten to know well, and observe up close. They are extraordinary individuals.

When writing about Anne a few years ago I came up with a term to describe people like her and Prof. Yunus. I call them “Humanitarian Giants.”

It may sound strange to call such a petit woman a “giant,” but I think the term is apt.

These are people who, by virtue of what they do, and how they do it, and above all what they accomplish, tower over the rest of us.

So, let me play amateur anthropologist and describe what characterizes this species.

They inspire awe, especially in those of us dedicated to humanitarian objectives.

But they don’t just inspire awe. They inspire each of us to do our personal best to advance the humanitarian agenda. Just by virtue of who they are, they “push” us to greater effort and better results for the poor.

Once they believe in something strongly, they are absolutely certain they can convince anyone to agree with them and get on board. If they don’t succeed in the first attempt to convince, they will try again, and again, and again. Usually they succeed.

Perhaps most of you have seen Anne in this convincing mode. Probably on occasion you have been the object of her attempt to convince you that this or that course was the best. As several people have said tonight, she is a force of nature!

Humanitarian Giants are not afraid to repeat the same story, over and over, and do it with equal passion each and every time. I get bored of telling that same story over and over. But they recognize that the basic story of an organization like Fonkoze works, and that it just needs retelling to as many people as possible, each time with a high level of passion. That’s what swells the ranks of those who are willing to share resources and effort to advance the cause.

These people are risk takers. In business and especially in philanthropy today, there is a lot of talk about the importance of risk-taking, and many people claim to be risk-takers, but in my experience precious few actually have the guts to take risks.

Humanitarian Giants are willing to take big risks. They realize, correctly in my view, that without taking the occasional big risk, great accomplishments and quantum leap advances are unlikely, and perhaps impossible.

When they take risks and they fail, they take full responsibility. When the risks turn out great, they share the credit generously with their team.

Humanitarian Giants know how meet people where they are. They treat everyone, no matter how rich or how poor, as their equal. Have you noticed that Anne never acts as if she is superior, or inferior, to anyone? Everyone she meets is a partner or a potential partner. To Humanitarian Giants, hierarchy among partners serves no constructive purpose.

These people live simply. They do not value or accumulate many material possessions. Their homes tend to be tastefully decorated but quite spartan.

Humanitarian Giants have the ability to, in one moment, demonstrate exceptional patience … and in the next moment, demonstrate exceptional impatience. I think you know what I mean!

They are tremendously courageous – physically, emotionally, spiritually.

They want their country, whether their native or adopted land, to shine and be seen as a star, rather than an object of sadness or pity. That is why I think Anne took the time to travel so much internationally and speak about Fonkoze, and serve in high level international working groups on Fonkoze’s behalf. She wanted people to know Haiti at its best, and what its true potential was, and is. It required a lot of time on planes, and a lot of wear and tear on her, but it was worth it.

Humanitarian Giants are relentless. They are persistent. They are, well, stubborn.

And finally, they have two qualities that are the most important of all. They demonstrate tremendous, almost unheard of, depths of empathy. When you hurt, Anne hurts almost as much, maybe more. When you experience joy, so does she. When you need something, Anne wants you to have it even more than you do.

Second, she is a fighter. She fights hard for what she thinks is right. She never gives up.

Probably most of you have seen her fight. You’ve been alongside her when she was doing battle for justice. Isn’t she something? Occasionally, some of us have been on the receiving end of her fighting spirit. It’s not easy!

But for Anne, she is never fighting against anything or anyone. She is fighting for an idea, and an ideal. Above all, for a result that advances the cause of justice.

Doesn’t Haiti need more deeply empathic fighters for justice? Doesn’t the world?

Going forward, we all may need to get in touch with our inner Anne Hastings, and explore the depths of our empathy for our fellow human beings, and our willingness to fight hard for humanitarian objectives.

A final reflection.

Money is important. Technology is important. Connections are important. But a wise friend told me that in cases of conflict, in the end, “The person who cares the most, wins.” I have come to believe it.

Nobody cares more than Anne. And when you look at what you have created here Anne, when you look around this room tonight, all I can say is, “You Won!”

Congratulations, Anne, and thank you.

More on the Practitioner-Researcher Interface

I have gotten lot of feedback on my previous post about the researcher/practitioner divide in microfinance. Needless to say, not all of it has been positive (though some has been very supportive).

I now see some omissions in the original post. As I mentioned in the comments section, there have been positive examples of researchers making efforts to set the record straight when the mainstream media reported in an inaccurate, harmful and sensationalistic way on their findings. I should have spent more time looking for the links to them but now I have published the best example, and others have given additional links. I still think researchers could have done more, but it is important to acknowledge what has been done.

Further, I should have mentioned a generous offer made by Dean Karlan to speak to practitioners assembled by Grameen Foundation about what research tells us about what works best in microfinance – something we intend to take him up on at some point. However, I believe that writing a paper on “lessons for practice,” as I have proposed, is considerably more cost-effective than one-off trainings and all the travel expenses they entail. That is why I was so pleased that Tim Ogden agreed to take this idea up.

I suppose that is what struck me so much by Tim Ogden’s positive and immediate response to my plea that he take on writing a “lessons for practice” paper – for whatever reason, he was willing to grant that an idea from someone outside the research community was valid and worthy of his time. I have not seen a lot of that to date. In my mind, he was implicitly admitting that there may have been something researchers had missed in terms of maximizing the public utility of their efforts. I found that refreshing.

Looking ahead, I think it is important to create a space where researchers and practitioners can work more collaboratively to advance learning, practice, and impact. Some years ago David Roodman and Beth Rhyne hosted a meeting that attempted to do that, but it was not successful. During that meeting I proposed, for example, that researchers offer to brief practitioners on upcoming research prior to being released, so we could ask questions, get clarification, think about implications, and prepare questions that would come our way from the media. The research community assembled that day turned down this suggestion.

Perhaps that meeting and my idea were ahead of their time. Today, Innovations for Poverty Action, the Financial Access Initiative and ideas42 are making worthy efforts to create this space. I give them an A for effort even though there is still clearly a lot of ground left to take. Alex Rizzi made some very concrete observations and suggestions on my earlier blog, which I commend and hope people take notice of. Those comments have prompted me to commit publicly to somehow find the money to translate the “lessons to practice” paper into several languages once it is complete.

An issue I may explore elsewhere relates to who is paying for research into the impact of microfinance, and whether that biases the results in any way. I need to give that more thought and I welcome input. I am told that the RCT-practice issue is also complex in the health care industry and there are many parallels with our own journey in the microfinance and financial inclusion arenas.

I am pleased to report that when I talked to Tim Ogden in London at the Financial Inclusion 2020 conference, about which I have had a blog recently published by the Center for Financial Inclusion website, he encouragingly confirmed his commitment to writing the “lessons for practice” paper. He noted that he, like so many of us, is subject to the demands of donors and doesn’t always get to do what he wants to right away. He also joked that he was uncomfortable with the ways that I had complimented him. (When I told Tim that someone had cautioned me against writing that my initial opinion of him was that he was “contrarian and pugnacious,” he smiled and said, “That’s the part I liked !”) I suppose that final point underscores that I really don’t understand researchers. Perhaps in time I will better comprehend what makes them tick.

In any event, I think it is important to underscore that while we may think about things differently and are subject to varying incentives, microfinance practitioners and researchers are on the same team fighting the same fundamental problem.

Fonkoze on World Toilet Day

In the circles I move in these days related to my work with Grameen Foundation and Fonkoze, one often hears that more people in the world own and/or have access to a cell phone than to a toilet. I am not sure of the significance. Perhaps this factoid is meant to draw attention to the proliferation of mobile phones, or to the stalled effort to ensure safe sanitation, or maybe to misplaced priorities. (And if it is the latter, is it commenting on the priorities of the poor, or of development planners?)

Anyway, yesterday was World Toilet Day, something that Anne Hastings of Fonkoze brought to my attention when we were exchanging emails on another topic. Later, I read an op-ed in the New York Times criticizing the Gates Foundation’s emphasis on solving the world sanitation crisis through inventing new toilets for future deployment around the world. The thesis was that there are many low-tech and affordable solutions that already exist and the focus should be on them.

I have some sympathy for this view. A simplistic over-emphasis on “gadgetry” has infected many humanitarian efforts lately. At the same time, I think it is dangerous to dismiss the potential of new thinking, and new thinkers, to come up with technologies to better serve the world’s poor and organizations that work directly with them.

A critical factor with deploying solutions to the poor – whether they be low-tech or high tech, digital or analog, 20th century or 21st – is the institutional capacity of grassroots organizations to explain new ideas and technologies to the poor and provide the financing and troubleshooting needed to optimize impact. This is why organizations like Fonkoze are so essential, especially in places like rural Haiti where there is such a paucity of strong private, public and humanitarian institutions. (I made some similar points about the challenges confronting the “financial inclusion” agenda in a recent blog.)

In any case, as I compose this I am en route to Haiti for a meeting of the Fonkoze Family Coordinating Committee (that I described in another recent blog) and for a celebration of Anne Hastings 17 years of service in Haiti. I will be reporting on all this in the days ahead. As part of this celebration, I have been re-reading and re-posting my four-part series on Anne that was published last year.

Fonkoze in the Midst of Transformations and Transitions

In my previous post – which generated a record 20 comments (not including my own), 747 views, and a fair bit of controversy – I promised to provide a separate update on my book and recent developments with Fonkoze. Here is that update. I will return to the issue of how research and practice relate in another post.

First, let me comment about the status of my book on Fonkoze. Despite claims to the contrary, I have not “ditched” it. The reality is more interesting and has three elements. First, I have come to a more realistic assessment of the time it will take to properly research and write something that does justice to the subject.

Second, Fonkoze is undergoing some important transformations in terms of its structure, strategy and staffing, and I believe it will be more appropriate to finish the book once those changes have played out. In particular, Anne Hastings stepped down as the CEO of SFF, the for-profit arm of Fonkoze, after 17 years of full-time work leading various Fonkoze institutions, and she was initially succeeded by a three-member management committee.

More recently, Matthew Brown, a member of that committee, was named as CEO by the SFF Board. The other two members of that committee, Dominique Boyer and Francis Ollivier, remain in their roles as COO and CIO respectively. Anne will be an active volunteer even as she has become the manager (and effectively staff director) of the Microfinance CEO Working Group that I am a founding member of. The Working Group is composed of 8 microfinance networks comprised of 250 of the world’s leading microfinance institutions that reach 40 million families. I see her appointment as a strong affirmation of the respect and influence Fonkoze has garnered well beyond the borders of Haiti, in large part due to Anne’s nonstop efforts spanning nearly two decades.

Third, I have been drawn into trying to shape the transformations Fonkoze is going through (in ways I detail below). In order to write even somewhat objectively about Fonkoze, time needs to pass after I phase out as an active volunteer for me to take up the book again in a serious way. (To give some idea of how active: I have been in Haiti every 8 weeks for the last two years.)

So, what have I been doing? Over the past year I have continued to Co-Chair the Fonkoze Family Coordinating Committee (FFCC), a high-level advisory group made up of board members and senior staff (drawn from all three organizations) that discusses and makes recommendations on important issues that impact multiple Fonkoze organizations.

My Co-Chair, Julian Schroeder, is one of the most extraordinary people I have ever met – a savvy businessman who is also a devout Christian, humble to a fault, reflexively optimistic and affirming of others, and when needed, very decisive and vocal. It’s been a terrifically challenging and satisfying assignment.

As one would expect in a high pressure endeavor, I have made, caused and observed some wrong decisions, hurt feelings, and frayed relationships. But overall, few if any deny that the FFCC has been a constructive force within the Fonkoze family. In many ways, the family of Fonkoze organizations is working very well, tackling vexing problems head on, and solving many of them. And what a learning experience it has been for me! With so many microfinance institutions splintering into non-profit and for-profit arms, this experience of enhancing coordination and managing a leadership transition has important lessons for a global audience.

In addition, I chair the Fonkoze Futures Committee, which is charged with raising the funds needed to properly recapitalize these organizations, all of which were badly drained (in human and financial terms) by the 2010 earthquake aftermath, ongoing losses by the micro-lending operations, and some calculated risks meant to benefit clients that did not pay off. Recently, the Futures Committee efforts paid off in a historic investment of $2 million in SFF by Digicel – a leading global communications provider with operations in 31 markets in the Caribbean, Central America and Asia Pacific. Some other promising trends are emerging, particularly in terms of SFF tracking to its planned pathway to breaking even in the not-too-distant future.

As my involvement with Fonkoze has deepened, I cannot deny that my ability to write objectively about the organization has been compromised to some degree, even as my knowledge of it has grown. Thus, I feel a need to taper down my involvement before taking up the book project again in a serious way. But this blog will continue in the meantime.